African freedom in Tudor England: Dr Hector Nunes’ petition

The letter above was sent by the Portuguese doctor, Hector Nunes, to the Queen to protest against the fact that he had been duped into buying an African man, not realising it was illegal to keep slaves in England. Nunes asks for the Queen to either force John Lax, from whom he bought the African man, to repay the money that Nunes spent or to force the African man to serve him for the rest of his life.

Modern English translation:

To the Queen’s most excellent Majesty

Your petitioner and faithful subject Hector Nunes, doctor of Medicine, most humbly complains unto your highness that one John Lax of Fowey in your highness’s county of Cornwall, Mariner, having an Ethiopian Negar [Negro] lately brought from the port of Santa Domingo in New Spain beyond the seas in or about the month of October now last past came unto the said petitioner [Nunes] and offered to sell the same Ethiopian unto your said petitioner as is the custom in Spain and Portugal and other Countries beyond the seas. And the said petitioner not knowing the laws and customs of this your realm of England, but thinking the laws to be the same here as in his own country (in Portugal) where he was born, bargained with the said John Lax and bought the same Ethiopian and for him paid unto the said John Lax the sum of four pounds and ten shillings of the full money of England. But now if it please your highness, the said Ethiopian utterly refuses to tarry and serve your said petitioner during his life according to the bargain made by the said John Lax with your said petitioner, so that he your said petitioner is likely to lose both the said Ethiopian and also his four pounds, ten shillings. In consideration of this and because your said petitioner has not any ordinary remedy at and by the course of the Common Law of this realm either to compel the said Ethiopian to serve him during his life or to recover his four pounds ten shillings again of the said John Lax. And thereafter for that your said petitioner being a foreigner and born out of this realm was ignorant of the laws here, may it therefore please you to grant unto your said suppliant your grace’s writ of public seal to be drafted unto the said John Lax commanding him thereby personally to be and appear before your highness’s committee of your honourable Court of Requests at a certain day and under a certain penalty there by your highness to be committed and appointed there and then to make promises upon his corporal oath [an oath ratified by corporally touching a sacred object, usually the gospels] And further to stand to and abide further order and direction in this matter as to your highness’s said committee [of the Court of Requests] shall form to stand with equity right and good compliance. And your said petitioner according to his bounden [sworn] duty does pray unto Almighty God for the prosperous state and long continuance of your highness.

(Source information: the image above has been provided courtesy of The National Archives, ref: TNA REQ 2/164 no. 117)

Hector Nunes' petition

The main source above gives examples of two related migrant groups: Portuguese conversos or Marranos (Jews, ostensibly converted to Christianity) and Africans. Hector Nunes, who wrote the petition in the above source, came to England from Portugal in the 1540s to avoid persecution for his Jewish faith by the Portuguese Inquisition (see also: ‘Blood libels, castration and Christian fears: opposition to Jewish citizenship’). There were at least eighty or ninety Portuguese Marranos in Elizabethan London.

The ‘Ethiopian Negar’ referred to in the petition was probably not from modern-day Ethiopia, as the term 'Ethiopian' was used broadly by the Tudors to refer to Africans. He is said to have come from ‘Santo Domingo in Nova Spayne’. 'New Spain' was a name given to the Spanish Empire in South America and the Caribbean, so this man had recently arrived from Santo Domingo, the city in the modern-day Dominican Republic. The Africans living in the Spanish Caribbean at this time mostly originated in Senegambia, the region of West Africa that lay between the Senegal and Gambia rivers.

Frances Drake's attack on Santo Domingo

As Nunes' petition dates from 1587, the African man is most likely to have arrived in England with Francis Drake, who attacked the city of Santo Domingo in 1586. On this voyage, Drake ransacked the ports of São Tiago in the Cape Verde Islands, Santo Domingo, Cartagena in Columbia and San Agustin in Florida. At every one of these ports, Africans, both men and women, ran away from their Spanish masters to join the English. An underlying cause of this migration was the war between England and Spain, 1585-1604, during which the English attacked Spanish ports where Africans were living and captured Spanish ships that had Africans on board. The Spanish and Portuguese had been transporting Africans across the Atlantic as slaves since the early years of the sixteenth century.According to a Spaniard named Pedro Sanchez, Drake ‘carried off 150 negroes and negresses from Santo Domingo and Cape Verde – more from Santo Domingo’. Africans in Santo Domingo may have believed they would find freedom in England. We know that one enslaved African named Juan Gelofe had remarked to William Collins in Mexico in 1572 that England must be a good country because there were no slaves there. Unfortunately many of these Africans, like many of the English, died when a terrible storm hit the fleet while they were anchored at Roanoke in Virginia in mid June 1586. John Lax, the Cornish sailor referred to in Nunes’ petition, may have met the ‘Ethiopian Negar’ on the voyage, or shortly after Drake’s fleet arrived in Portsmouth on 28 July 1586. He was somehow able to persuade him to travel to London with him, where he then sold him (illegally) to Hector Nunes.

Africans in Tudor England

Although they are not mentioned in this document, we also know there were other Africans in the Nunes household at this time. They had probably come from Portugal: 10% of the population of Lisbon was African at this time. There were at least 350 Africans in England during the Tudor and early Stuart period (1500-1640). It is difficult to know exactly where in Africa they came from because Tudor records rarely record this, usually referring to them as ‘blackamoors’ or using other vague ethnic descriptions like the ‘Ethiopian Negar’ in this document. That said, most of them probably came from North and West Africa, the regions that had most contact with Europe at this time. They settled across the country, with individuals appearing from Edinburgh and Hull to Plymouth and Truro – but with larger numbers ending up in the port cities of London, Southampton, Bristol and Plymouth. Some came as a result of privateering, captured from Spanish or Portuguese ships or cities, some in the households of royalty or merchants from southern Europe, some came back with English merchants trading to Africa. Many worked as domestic servants, but some became financially independent, like Reasonable Blackman, a silkweaver in 1590s Southwark.

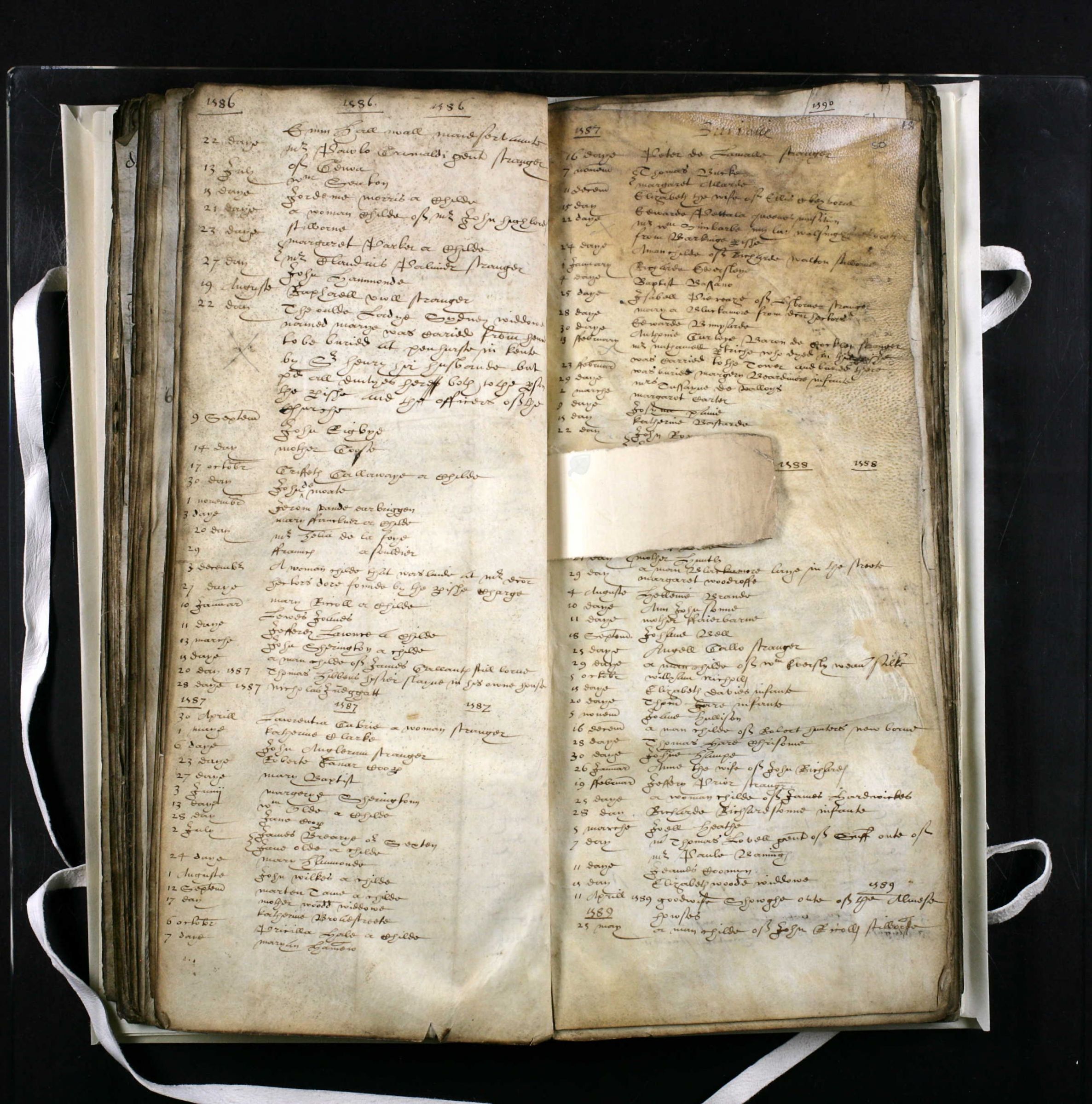

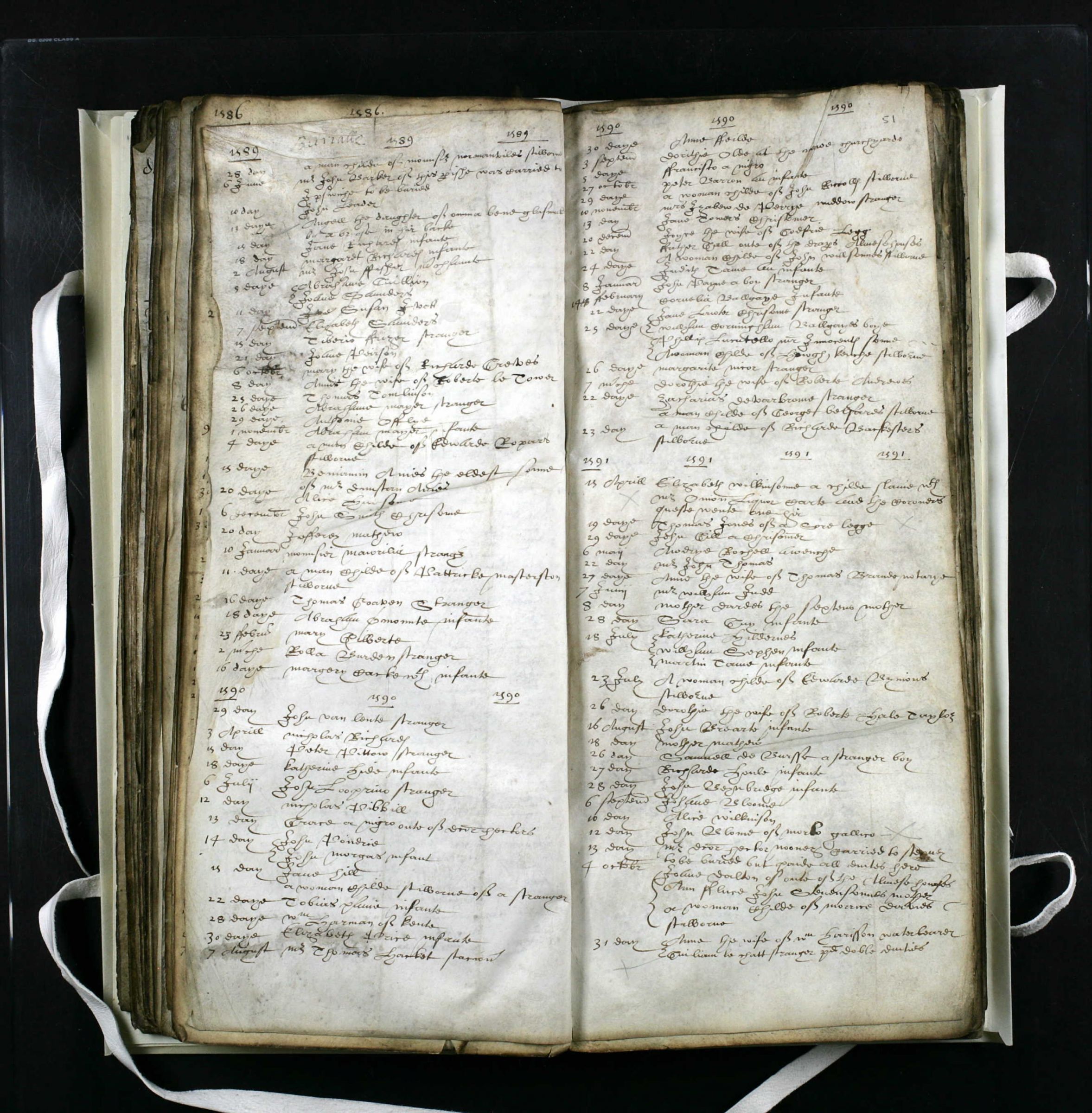

The photos show the burial records of Mary (28 January 1588) and Grace (13 July 1590), Hector Nunes' African servants (Courtesy of www.ancestry.co.uk)

Portuguese Jews in Tudor England

Hector Nunes himself had fled persecution in Portugal. He was born in 1520 in Evora, to the east of Lisbon, in south-central Portugal. His family were among those Jews who had been forcibly baptised in 1497 by order of King Manuel I. He studied medicine at Coimbra University in the early 1540s. Once he was qualified he decided to leave Portugal to escape the the Inquisition that had been established in Portugal in 1536. In 1549 he was living in London, in the parish of St Olave, Hart Street and in 1554 he was elected a fellow of the College of Physicians, meaning he was able to work as a doctor in London. He also became a successful merchant, diplomat and spy. He was one of the small community of less than 100 Marranos living in Tudor London (plus a few in Bristol, like his uncle, Henrique Nunes, who was also a merchant and physician). Some of them had travelled directly from Portugal. Others had first escaped Portugal for the Netherlands, but were forced to move on again after Charles V issued a decree that all ‘New Christians’ should quit Antwerp in 1549. This was part of a wider diaspora, in which Jews fled the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal, heading for North Africa, Turkey, Italy and South America besides the Netherlands and England.

Jews were officially expelled from England by Edward I in 1290, and readmitted under Cromwell in 1656. In the interim, however, small numbers of Jewish people continued to live in England, and were tolerated, as long they concealed their true faith. Nunes’ true identity was something of an open secret. In 1588, Pedro de Santa Cruz, a Spanish merchant who had been a prisoner in London named various Marranos in London to the Spanish authorities, including Hector Nunes and his brother-in-law Ferdinando Alvarez: ‘it is public and notorious in London, that by race they are all Jews, and it is notorious that in their own homes they live as such observing their Jewish rites.’

Openly practising Judaism was, like any heresy, punishable by death. Anti-Semitic ideas were prevalent in the fervently Christian atmosphere of Tudor England. These reached fever-pitch when the Marrano Dr Roderigo Lopes was hung drawn and quartered in 1594 on the charge of conspiring to poison Queen Elizabeth. However, in stark contrast to their treatment under the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal, Jews were largely tolerated in Elizabethan England.

Legal documents as historical sources: the Court of Requests

Nunes’ letter (in the main source above) is a petition to the Court of Requests. This was one of the royal courts that met at Westminster. It was established in 1485 as an offshoot of the King’s Council, deriving from the King’s ancient right to give legal judgements. The Court of Requests was intended to provide easy access to the royal justice for poor men and women. In reality, a wide variety of people were attracted by its relatively cheap and simple procedure. It became particularly popular with well-to-do merchants like Hector Nunes. In fact, the court received so many petitions that they were not always dealt with swiftly. When Elizabeth I complained to Walter Haddon, one of the court’s officials, that his boots smelt he replied: ‘I believe, madam, it is not my new boots that stink, but the old petitions which have been so long in my bag unopened.’ The Court ceased to function after its Privy Seal was removed to Oxford by Charles I at the beginning of the Civil War in 1642.

Nunes’ petition is made directly to the Queen, as he explains his problem cannot be solved under the Common Law. The petition was the first step in the legal process, in which the petitioner, with the help of a lawyer, set out his complaint and his right to be heard by the Court (like Nunes, who explained he could find no remedy under the Common Law). This would then be followed by an answer from the accused, in this case, John Lax. Nunes would then be given a chance to respond to Lax’s answer, then a rejoinder from Lax, before their lawyers drafted a list of questions which would be put to witnesses, who would testify or make depositions before the court passed judgement and issued a verdict, known as an order or decree. Unfortunately, the rest of the papers related to Nunes’ case were not kept together with the one in the main source, and not all the papers of the court survive, so we do not know what other statements or testimonies were made, or what decision the court made in the case. Despite this, legal documents such as these give us a lot of interesting details about people’s lives, especially relatively ordinary people who did not write letters or diaries.

Making lives: from slavery and exile to freedom in England

Unlike in Spain and Portugal and their empires, Africans were not enslaved in Elizabethan England. Nunes claims he thought that the laws of England were the same as the laws of Portugal where the Ordenações Manuelinas made slavery legal. But no such laws were passed in England. As Nunes says, he has ‘not any ordinary remedie at and by the course of the Comon Law of this realme eyther to compell the said Ethiopian to serve him duringe his life or to recover his four pounds ten shillings.’ A court ruling in the Cartwright case of 1569 declared that ‘the air of England is too pure an air for slaves to breathe in’. In his Description of England, written in 1587, the same year as Nunes’ petition, William Harrison explained: ’As for slaves and bondmen, we have none; nay such is the privilege of our country by the especial grace of God and bounty of our princes, that if any come hither from other realms, so soon as they set foot on land they become as free in condition as their masters, whereby all note of servile bondage is utterly removed from them’.

The African man’s refusal to ‘tarry and serve’ Nunes suggests that he realized that he was free in England. As we don’t know his name it is hard to trace what happened to him after he left Nunes’ household. However, from a range of other sources, including parish registers, other court records, household accounts, tax returns, letters and diaries, we know something of the experiences of other Africans in England at this time. They were baptised, married and buried in the Church of England. For example, Grace and Mary, African women working for Hector Nunes, were buried at St. Olave’s, Hart Street, London in 1588 and 1590. Some married other Africans, some married English people. They had children. They found work, for which they were paid wages. They were allowed to testify in court. Their free status makes for an interesting contrast to their treatment in other parts of Europe at this time, as well as in English colonies later in the seventeenth century. Although the status of Africans in the early English colonies was not set in stone, by the 1660s, laws had begun to be made in Virginia and elsewhere fixing their position in society as hereditary slaves, who were not allowed to marry English people nor to testify in court.Africans and Jewish exiles were able to make lives in Tudor London. Nunes' medical skill allowed him to flourish in his career as a doctor. His connections with Spain and Portugal allowed him to build a successful network both for trade as a merchant and as a diplomat and spy. His Marrano identity did not stop him from achieving any of these things, though he did have to conceal it in order to be accepted into Tudor society. As for the man Nunes purchased, he was free, as other Africans in Britain at the time, to try to live the life he pleased.

The story of Dr Hector Nunes and the man he tried to purchase shows how multiple peoples, cultures and expectations can collide during migration. It also shows how one migrant group may not, necessarily, identify with the needs of another just because of their shared migrant status. With that in mind, consider the following questions:

- How do you feel about Nunes’ petition? Should migrants be allowed to protest against the laws in the country they migrate to? Should they not just accept what they find?

- Who is at fault, in your eyes, in this case? Is it Nunes? John Lax? What would you have done if you were overseeing this case?

- Was it hypocritical for people to be automatically free in England but enslaved in its colonies? How was this system justified at the time?